7 things that Sung Vespers can teach us about life

- angelamrocchio

- Jan 17, 2024

- 8 min read

Image by EPA: pre-Vespers discussion by Catholic Archbishop of Westminster and Anglican Bishop of London at an historic Vespers held in Hampton Court, February 2016

The Psalms are at the heart of Hebrew and Christian worship.

Predating the birth of Christ by about a thousand years, they were were sung during worship in the Temple. Animal sacrifice and singing to God were two sides of the same coin. Animal sacrifice symbolized the offering of carnal things to God, while chanting of the psalms expressed the offering of our spirits to God.

Fast forward to the persecution of the early Christians, starting with the Great Fire of Rome and Emperor Nero in 64 A.D. Diamonds are made under pressure, and the next 250 years of persecution gave material cause for profound faith and heroism. The perpetuation of such devotion was, in turn, a foundational impetus for many to "flee" to the desert for a life of prayer and penance. In fact, the desert life of asceticism was viewed as the next best sacrifice to God after martyrdom.

“Seven times a day I praise you” (Psalm 119: 164)

When the persecutions were officially ended in 313, even more Christians took up the desert life, and it was here that the praying of the Psalms in form of the Divine Office (or Liturgy of the Hours) began. “Seven times a day I praise you,” the psalmist wrote. The desert fathers (and mothers), followed the Jewish custom of offering certain prayers at set hours of the day. They memorized all 150 psalms by heart and prayed them over the course of a week (and some, over the course of a single day!). Sometimes they gathered in small groups to pray the Hours together.

The Office has undergone plenty of alterations over the ensuing centuries, but its core is still the same: fixed times during the day for offering thanks and praise to God, primarily by praying the Psalms. Priests, deacons, and certain other religious persons are bound to this day to pray the Office regularly. (Monastic communities place particular emphasis on chanting the Office together. If you have a monastic community near you, it is worth a visit just to hear them!)

Vespers, or Evening Prayer, is one of the two chief Hours (the other is Lauds, or Morning Prayer). The prayer follows a precise rubric including certain psalms, the Magnificat, and other antiphons, prayers, and scripture readings. (Side note: Anglican Evensong is a form of the Office which combines Vespers and Compline or Night Prayer.)

This article is devoted to Vespers in particular, as it is the most common Hour which a parish will celebrate in community. It is the hope of the ICA to encourage the observance of this practice more widely. The article, however, applies not only to Vespers, but to the whole Office.

And now, without further ado...7 things that Sung Vespers can teach us about life.

1. Seek God in all circumstances.

The Psalms are filled with lively imagery and raw emotion, and give full voice to our challenges and dreams. They do not “sugar coat” the trials of man, or belittle our cares as unworthy of divine attention. Rather, they give full voice to good and evil, bringing our ongoing human adventure to the throne of God himself.

In emphasizing the height and depth and breadth of human experience, the psalms teach us to seek God in all circumstances. God isn't concerned with just the "good" parts of ourselves and our lives; God desires all of us: the good, the bad...and the ugly.

2. Anyone can sing!

Let me say that again. Anyone can sing! Most members of religious communities don't read music. The tones used for singing the psalms in the Office are actually meant for non-musicians. (I remember Dom Saulnier telling us that those who try to join the monastery in Solesmes on account of Gregorian chant never last long, because most of the monks are not musicians, and the singing is always sub-par. Singing the Office together eight times a day will become unbearable without a higher purpose to subsume the musician's sensibilities.)

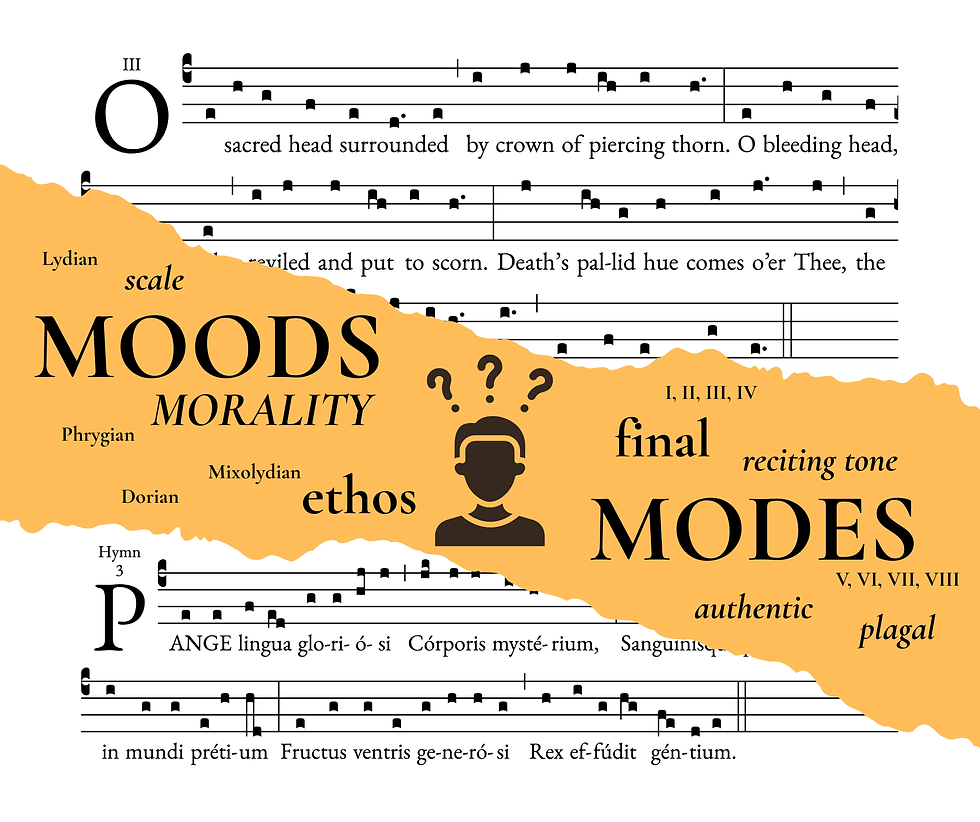

Psalm tones aren't all that different from hymns. Both have a set melodic formula that repeats over and over, with different words each time. The difference? Psalm tones have no meter; they can fit any line of text, short or long, by means of an elastic reciting tone (the pitch on which the majority of the text is sung) which expands and contracts in proportion to how much text needs to be sung.

Oh - I just mentioned hymns, didn’t I? Hymns are an integral part of the sung Office too. In the Office, the hymn is the liturgical action (rather than simply accompanying the liturgical action, as happens during a procession during the Mass). So, rather than tailoring the number of verses to the length of the liturgical action and chopping off the rest of the song, in the Office you always get to sing the entire hymn!

Fun Fact: the Vespers hymn for the Nativity of Saint John the Baptist (which was in liturgical use in the early eleventh century, if not even earlier) is the origin of our modern system of solfège! Ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la (ut was replaced by do in the eighteenth century).

"Ut queant laxis" is the Vespers hymn for the Nativity of Saint John the Baptist; there are five verses of the hymn altogether

3. An exercise in living in peace with our "neighbor".

“Love your neighbor as yourself.” When singing the Office in community, we pay attention to what the others are doing. We breathe together. We sing together. (No one wants to be that person with the half-second solo because they started singing the verse too early.) We seek to synchronize our breath and speech pattern to those of our neighbor, and our neighbor does the same to ours.

Learning to sing, in choral singing, is not only an exercise of physical hearing and of the voice; it is also an education in inner hearing, the hearing of the heart, an exercise and an education in living and in peace. Singing, whether in unison, in a choir and in all the choirs together, demands attention to the other, attention to the composer, attention to the conductor, attention to this whole that we call music and culture. Hence, singing in a choir is an education in life, an education in peace, it is "walking together." — Benedict XVI at Mirabello Castle, July 2007

Singing una voce (that is, in one voice) is a tangible expression of the Mystical Body of Christ. We are many members with unique functions, yet together comprise one body, the Church. And what one member does, has the power to affect all the other members.

4. Life is so much bigger than me.

The first account of a full sung Office (Vigils, Matins, Terce, Sext, None, and Vespers — but not Prime or Compline) dates all the way back to c. 385, when Etheria, a Spanish abbess, made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and drew up a detailed report of the liturgies there. One and a half centuries later, Benedict of Nursia codified into his Rule eight canonical Hours (seven during the daytime, and one during the night), with the precise number and arrangement of psalms.

Paul exhorted the Thessalonians to "pray without ceasing." Collectively, communities all over the world, at all hours of day, pray the Office, and thus fulfill his instruction. When we pray the Office, we participate in the perpetual and universal prayer of the whole Church.

Leaves from a book of hours: calendar pages for May and June, c. 1510 France, Rouen

5. Speaking and listening are both part of a relationship with God.

Have you ever wondered why so many churches have seating arranged with two sides facing each other, rather than facing the altar? That, my friend, is directly related to the singing of the Office. Normally, when the psalmody is sung, the right and left sides alternate in what we call antiphonal singing. One side takes the even verses, and the other takes the odd verses. While one side sings, the other listens.

This method of singing is also very, very old. We find it in the Old Testament at the completion of building the wall around Jerusalem. “I had the administrators of Judah go up on the wall, and I arranged two great choirs. The first of these proceeded to the right, along the top of the wall…The second choir proceeded to the left…Both choirs took up a position in the house of God.” (Neh 12:31-40)

Antiphonal singing was a part of singing the Office in early Christian monasticism (remember the desert fathers we just learned about at the beginning of the article?). In the early fourth century, it gained favor with the mainstream public as well. In fact, its allure of lively active participation earned it a special role in defeating the Arian heresy, which was up til then spread by the means of hymns. Talk about the power of music!

Speaking and listening are both essential to any healthy relationship. Some people have to work more at expressing themselves, while others have to work harder at listening. No friendship can exist without both parties exercising these qualities. Antiphonal singing shows us that speaking and listening are essential parts of a conversation with God, too.

photo by Jorge Royan: antiphonal singing at Cistercian Abbey in Heiligenkreuz Abbey, Austria

6. Slow down.

If you've ever been on retreat at a monastery where they chant the Office together daily, you know exactly what I'm referring to. We go about our lives thinking there is never enough time to do all the things we want to do. And then we watch religious communities devoting hours every day to prayer. When the bell indicates the next Hour to be prayed, they drop everything immediately and hurry to the chapel. "Just let me finish one more thing and then I'll join you," isn't a part of their vocabulary.

Chanting the Office calms and refreshes the spirit. Perhaps this is part of the attraction of antiphonal psalmody, which we just learned about in the previous point. When we step away from our daily activities to pray, we come back to them with a new clarity and peace. I'm reminded of a sign that was hanging near a chapel that I visited frequently many years ago. "Praying takes time. The saints pray a lot, and get more done in less time."

7. Cultivating a path to interior silence.

Have you ever listened to a reader who runs all the sentences together? It's intolerable. Pauses are necessary. They give the listener the meditative space to digest what has just been spoken, and to link thoughts together.

There is a particularly interesting observance of the pause in singing the Office. While we would expect to find a pause at the beginning of each new sentence/verse, the most prominent pause is actually observed in the middle of the verse. Why? The answer lies in the compositional style of the psalms. “Parallelism” is a style of poetry in which the words of two or more lines of text are directly related to each other in some way. A psalm verse is composed of two lines, each related to each other in this poetic parallelism. The mediant pause (at the middle of the verse) provides a moment to absorb the connection between the related thoughts of each verse half.

Look at how this works in Psalm 19:1-2.

Side A: The heavens are telling the glory of God; (mediant pause)

and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.

Side B: Day to day pours forth speech, (mediant pause)

and night to night declares knowledge.

It has been said that Gregorian chant leads a person to silence. This is certainly the case in psalmody. It doesn't come without a concerted effort, however. The singer will wrestle internally in the beginning. There is a strong temptation to rush through the mediant pause as quickly as possible. Perhaps it is due to cultural expectations that every moment must be filled with productive activity. Perhaps we have trained ourselves to avoid silence so that we do not have to face the noise and the chaos inside ourselves.

Whatever the reasons may be, it takes discipline to master the pause. Remember what I said at the beginning: diamonds are made under pressure. Once the singer has mastered the pause, a transformation begins. The singer discovers a realm where it is safe to be silent, and is made ready for interior conversation with the Divine.

Join us for our next lecture with Dr. Horst Buchholz. Singing around the Clock: Celebrating the Liturgy of the Hours in Parishes, an historic overview with parochial applications and useful tips on how to point and chant the psalms, focusing on Sung Vespers.

Register here.

Register here.

The mission of the International Chant Academy is to keep the beauty and meaningfulness of Gregorian Chant and Early Sacred Music alive and relevant. We foster understanding of these art forms, and teach the musical and vocal skills necessary to excellent performance.

Visit our website.

Comments